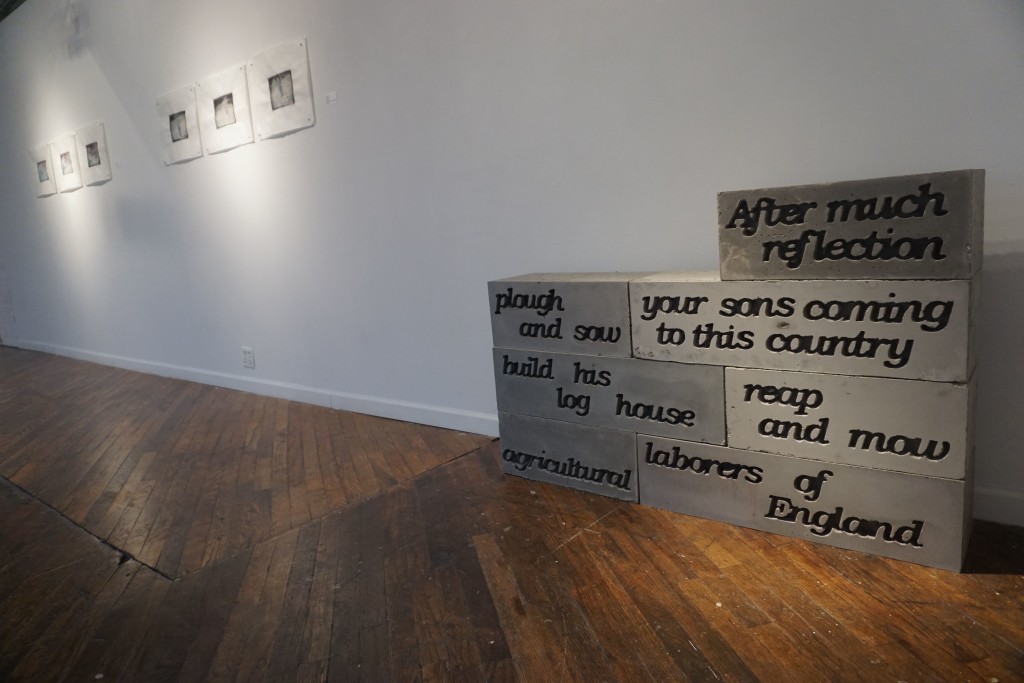

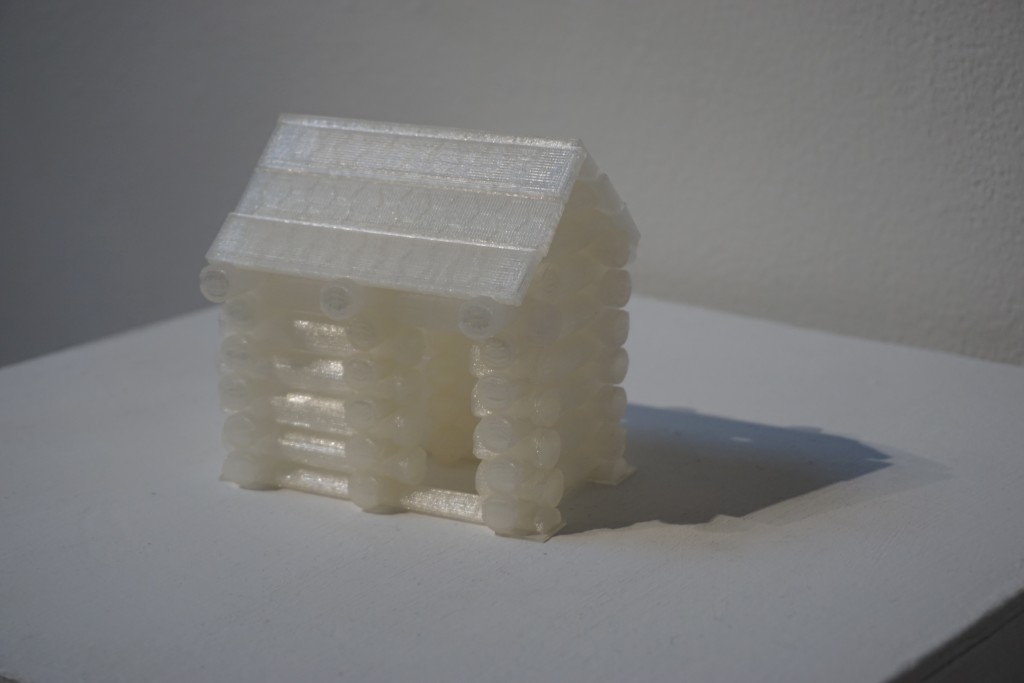

When we imagine a visual artist using technology in their work, we may think of finished products like glitch art, 3-D printing or intricate laser cutting. But Atlanta-born artist Mary Stuart Hall is a tech artist with a different goal in mind. She doesn’t aim to shock us with flashing lights or a big, showy reveal. While technology plays a large role in her work, it’s a tool to enhance the poetry and power of the real idea taking center state: language and the symbols we assign to it.

When we imagine a visual artist using technology in their work, we may think of finished products like glitch art, 3-D printing or intricate laser cutting. But Atlanta-born artist Mary Stuart Hall is a tech artist with a different goal in mind. She doesn’t aim to shock us with flashing lights or a big, showy reveal. While technology plays a large role in her work, it’s a tool to enhance the poetry and power of the real idea taking center state: language and the symbols we assign to it.

How we communicate is one of the most complex topics an artist could explore, and it has fascinated Hall since the beginning of her artistic career. She builds completely unique machines around the singular (yet immensely complicated) idea of words. Forever a student and addict of deep conversation and novel ideas—she started a post-graduate supper club just to fill the void of no longer being challenged in an academic setting—Hall is always hungry to learn and find new ways to create. Even as technology changes and becomes more accessible, the machines she employs always manage to feel gentle and restrained. Her hand-built mechanisms serve only to enhance the poetry of her work by allowing it all to be interactive and personal.

Hall talked with CommonCreativ about the role of technology in her work as well as how she always winds up needing to call on a friend—or even make a new one—to start her next project.

CommonCreativ: When did you start making art?

MSH: I really didn’t start creating art seriously until college. I was always interested in photography and started off as a photo major at Sewanee, but then took a sculpture class that changed everything for me. I realized I loved making things and particularly loved working through conceptual ideas. It was a whole new world, and I still can’t get enough of it!

CC: How has technology influenced your work?

MSH: Technology really entered my work in graduate school. While I was working on my Masters in Art Education at UGA, I took a lot of classes in their Art-X department. I was blown away by the fact that I could make something do something. While I never want the technology to override the poetry, I love finding ways that it can support a concept. I do think we have a tendency to fetishize technology and often are drawn to pieces that appeal to a desire for shock and awe rather than create subtle poetry. I want the technology to fade into the background of an emotional experience for the viewer.

CC: I love your inclusion of player pianos in your installations—there’s such a tenderness and simplicity to them that’s interesting when paired with the digital aspects of your pieces, such as in your piece Acoustic Waypoints. How did you decide to include them in your work?

MSH: Long before I completed Acoustic Waypoints I bought the player pianos out of curiosity. I didn’t have a plan for them, I just thought they were interesting. I took a studio class at UGA and developed a project that would eventually become Acoustic Waypoints, although it took a few turns before it got there. I just loved how they feel nostalgic but unsettling. At the same time, they use a binary code. So many things in our technologically infiltrated world are driven by binary code. This simple machine predated all of that and can inhabit so much emotion. While language is encoded from a cultural perspective, I was fascinated with taking that literally and making it into a code (braille) in order to mediate another experience (sound). It became an expression of text that removed the cultural encoding in some ways and allowed for an entirely different emotional experience.

CC: Do you construct all the machines that are included in your pieces?

MSH: I do, however I have great teachers and friends who help when I need it. With each new project there are new things to learn. I seem to have a knack for picking something that requires a technique I’ve never tried before, so I end up learning from some amazing people. The process of finding people who have expertise in a certain area or who are willing the share their knowledge of technology with me feels like such an important part of the project. It can even change the direction of a final piece. I’m very grateful to the people who support me as I continue to build my skills.

CC: How did text become the central focus of your art?

MSH: I really became interested in art because I wanted to explore how we create meaning, both with materials and with the specific content they reference. Text has an amazing ability to both hold meaning and generate meaning. The idea that we can’t have a thought without the word for the thought blows my mind. Whether or not you agree with that statement, and there are certainly linguists on both sides, it’s clear that the symbolic meaning of language and how it functions as a part of cognition is an incredibly complicated and fascinating process. On top of all of that, we rely on text to mediate information and communication. Finding ways to manifest that process artistically is a challenge I relish.

CC: How do you feel your work has evolved over the years?

MSH: I think the ideas that brought me to art haven’t really changed that much. I love working with materials that convey emotion, and that make us think about how we generate meaning and have cultural and personal relevance. That being said, the new technology that has come available in the years since I graduated from college has changed everything. The accessibility of technology has sent me in new and exciting directions.

CC: Tell us about Night School. Is that something you’re still involved with?

MSH: I started Night School with a few friends over four years ago. We’ve had some long hiatuses but it continues to bubble up and is one of my favorite things that I do. It’s basically a supper club with a creative prompt. The prompt is meant to be a jumping-off point—wherever people decide to go with it is up to them. Sometimes it’s interesting to zoom in on a tiny detail or some tangential connection. While creating complete works of art is great, it’s not required. The prompt is meant to spark our curiosity; some people bring in articles, make zines, bring in a book, really anything. One of the best things about having a prompt running around your head is that it makes you pay attention. All the sudden things have a new significance because they might connect to the prompt. I would love to see the group of people grow and see what else can come out of our conversations.

CC: What are you working on at the moment?

MSH: I really see The Topography of Text as a larger project that I plan on continuing to develop. I’m continuing to work with the concrete and imagery in The Topography of Text. Be on the lookout for future developments this year.

You can view more of Mary Stuart Hall’s work on her portfolio or Vimeo channel.